Forgotten Princess of Undivided Punjab- Bamba Duleep Singh

Princess Bamba was born into a proud royal lineage as the granddaughter of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the founder of the Sikh Empire in Punjab, India. She was the eldest daughter of the exiled Maharaja Duleep Singh and Maharani Bamba Muller, and the third of their six children.

Her elder brothers were Prince Victor and Prince Frederick, while her younger siblings were Princess Catherine, Princess Sophia, and the youngest, Prince Edward.

She was born on September 29, 1869, in England and was baptised Princess Bamba Sophia Jindan Duleep Singh. She was named “Bamba” after her mother, “Sophia” after her enslaved Ethiopian maternal grandmother, and “Jindan” after her paternal grandmother, Maharani Jindan Kaur.

Her early education took place privately at Elveden Hall in Suffolk, where she spent her childhood in an aristocratic lifestyle under the care of her governess, Miss Date, and surrounded by domestic staff, including ladies’ maids and valets. Outside, the vast gardens were filled with exotic birds and animals, providing her with a truly lavish and royal upbringing.

Growing up, Princess Bamba witnessed the gradual decline of her family. Her father’s extravagant lifestyle, combined with his growing criticism of the British government, placed great financial and emotional strain on the family. This ultimately forced him to sell their possessions, including Elveden Hall, and in 1887, he set sail for India with the family.

En route to India, at Aden, her father and the family were arrested on the orders of the Viceroy of India, who feared that Maharaja Duleep Singh’s presence in India would cause unrest. After two weeks of arrest and negotiation, the Maharaja, given no choice, was forced to send his family back to England while he departed for Paris to gather evidence against the British Raj.

The upheaval deeply affected the eighteen-year-old Princess Bamba, who openly started to express her resentment towards the British government. That same year, on September 18, her emotionally distressed mother passed away, and the children came under the care of Arthur Oliphant, appointed by the Palace. His role was not only to look after them, but also to report everything the children said back to the Palace.

After Maharani Bamba’s death, Arthur arranged for the children’s education. Princess Bamba and Princess Catherine were sent to Somerville College, Oxford, where Bamba faced challenges in French but excelled in grammar. Despite her efforts, she was ultimately unable to complete her education. Upon returning to London, she lived at Hampton Court with Princess Catherine and Princess Sophia, spending much of her time attending concerts and operas.0

Headstrong and known for her short temper, Princess Bamba, at twenty, had challenged the Palace and the then British-Indian Government for recognition of her title and rights as heir to the Sikh Kingdom. She was successful in securing a £22,000 settlement, a £600 annual allowance until March 1894, and an additional £10,000 to be granted upon her marriage.

In 1893, she suffered immense emotional stress, as she lost her thirteen-year-old brother, Prince Edward and, later that October, her father, Maharaja Duleep Singh, also died in Paris.

In 1902, Princess Bamba travelled to Chicago to study medicine at Northwestern University, but the school closed after the trustees decided that women as doctors were not successful. Disappointed, she returned to London and frequently expressed her longing to visit India.

That same year, Edward VII was set to be crowned as King of Great Britain, ruler of all British domains beyond the seas, and Emperor of India. Sensing an opportunity, Princess Bamba and her sisters applied for the passes to attend the coronation which was to happen in India at Delhi. Their request was initially ignored, as the Duleep family was banned from entering India.

Princess Bamba demanded a written explanation for their refusal and in response, the Secretary of State for India stated that, due to time constraints, it would be impossible to provide them with suitable accommodation and to make arrangements for their reception. He urged them to postpone their trip. In effect, this meant they were no longer officially banned from traveling to India. Princess Bamba took the opportunity and without a delay, in 1903, she made the arrangements and along with Princess Catherine travelled first, while Princess Sophia followed on a separate ship.

In India, they were warmly welcomed by Punjab’s chiefs and the aristocratic Sikhs, who still held their great-grandfather in high esteem. The sisters travelled to neighbouring cities, where they met their father’s cousins. They embraced their heritage and listened to stories of their royal lineage and its decline.

In Lahore, Princess Bamba purchased a residence in the Shalimar Gardens and appointed Pir Karim Baksh, known as Pir Ji, as her household manager and translator. During her stay, she once fell ill and feared she was being poisoned, prompting her sister, Princess Sophia, to visit. While in Lahore, Princess Bamba and her sister attended ‘parda’ parties, enjoyed dressing in elegant sarees, and supported revolutionaries such as Lala Lajpat Rai in their struggle against colonial rule.

In 1915, Princess Bamba met Lieutenant Colonel David Waters Sutherland, an Australian-born doctor and professor. At the age of forty-six, she married him and received the promised £10,000 settlement from the Government. Three years later, her elder brother Victor passed away, but wartime restrictions prevented her from attending his funeral.

In 1924, Princess Bamba, along with Princess Sophia, travelled to Nasik to collect their grandmother’s remains from the banks of the Godavari River and brought them to Lahore, placing them beside their grandfather Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s tomb. She also assumed responsibility for her brother Frederick’s art collection after he died of a heart attack in 1926, donating part of it to museums in England and bringing the rest to Lahore, where it was kept in Lahore Fort as the Princess Bamba Collection.

Princess Bamba later faced the loss of her husband in 1939, followed by her sisters Catherine in 1942 and Sophia in 1948. Honouring Sophia’s wishes, Bamba took her ashes to India and, in 1949, travelled to Kassel, Germany, to place Catherine’s ashes beside her governess, Lina Schafer’s grave.

She spent her final years at her Lahore home, known as “The Gulzar”, and died of heart failure on March 10, 1957, at the age of 89. She was buried as Princess Bamba Sutherland in a Christian cemetery. Sadly, due to the Partition, no Sikh attended her funeral. Pir Ji conducted a simple service, placing roses from her garden on her grave, with a gravestone inscription she had likely chosen herself:

‘Farq-i-shahi o bandagi barkhast,

Choon qaza-e navishta aayad pish

Gar kisi khak-i murda baz kunad,

Na shanasad tavangar az darvish.’

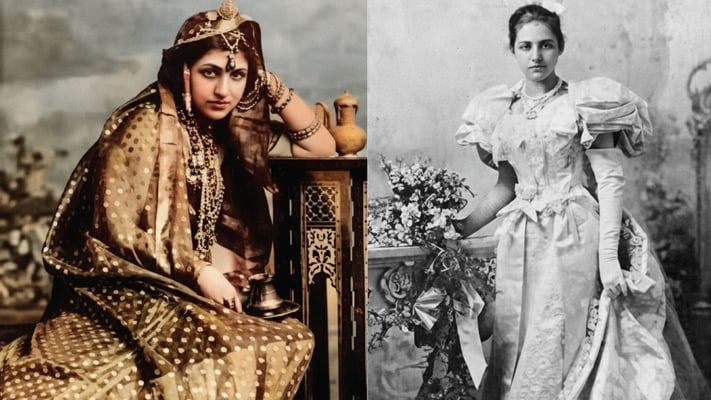

Until her last breath, Princess Bamba held Punjab in her heart as her sacred inheritance, commanding respect as its rightful Queen. With sharp features and a dusky complexion, she embodied a fierce and unyielding spirit, a living testament to the legacy of her ancestors, whose courage and dignity she carried forward with unwavering pride.

Princess Bamba was born into a proud royal lineage as the granddaughter of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the founder of the Sikh Empire in Punjab, India. She was the eldest daughter of the exiled Maharaja Duleep Singh and Maharani Bamba Muller, and the third of their six children.

Her elder brothers were...

Princess Bamba was born into a proud royal lineage as the granddaughter of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the founder of the Sikh Empire in Punjab, India. She was the eldest daughter of the exiled Maharaja Duleep Singh and Maharani Bamba Muller, and the third of their six children.

Her elder brothers were Prince Victor and Prince Frederick, while her younger siblings were Princess Catherine, Princess Sophia, and the youngest, Prince Edward.

She was born on September 29, 1869, in England and was baptised Princess Bamba Sophia Jindan Duleep Singh. She was named “Bamba” after her mother, “Sophia” after her enslaved Ethiopian maternal grandmother, and “Jindan” after her paternal grandmother, Maharani Jindan Kaur.

Her early education took place privately at Elveden Hall in Suffolk, where she spent her childhood in an aristocratic lifestyle under the care of her governess, Miss Date, and surrounded by domestic staff, including ladies’ maids and valets. Outside, the vast gardens were filled with exotic birds and animals, providing her with a truly lavish and royal upbringing.

Growing up, Princess Bamba witnessed the gradual decline of her family. Her father’s extravagant lifestyle, combined with his growing criticism of the British government, placed great financial and emotional strain on the family. This ultimately forced him to sell their possessions, including Elveden Hall, and in 1887, he set sail for India with the family.

En route to India, at Aden, her father and the family were arrested on the orders of the Viceroy of India, who feared that Maharaja Duleep Singh’s presence in India would cause unrest. After two weeks of arrest and negotiation, the Maharaja, given no choice, was forced to send his family back to England while he departed for Paris to gather evidence against the British Raj.

The upheaval deeply affected the eighteen-year-old Princess Bamba, who openly started to express her resentment towards the British government. That same year, on September 18, her emotionally distressed mother passed away, and the children came under the care of Arthur Oliphant, appointed by the Palace. His role was not only to look after them, but also to report everything the children said back to the Palace.

After Maharani Bamba’s death, Arthur arranged for the children’s education. Princess Bamba and Princess Catherine were sent to Somerville College, Oxford, where Bamba faced challenges in French but excelled in grammar. Despite her efforts, she was ultimately unable to complete her education. Upon returning to London, she lived at Hampton Court with Princess Catherine and Princess Sophia, spending much of her time attending concerts and operas.0

Headstrong and known for her short temper, Princess Bamba, at twenty, had challenged the Palace and the then British-Indian Government for recognition of her title and rights as heir to the Sikh Kingdom. She was successful in securing a £22,000 settlement, a £600 annual allowance until March 1894, and an additional £10,000 to be granted upon her marriage.

In 1893, she suffered immense emotional stress, as she lost her thirteen-year-old brother, Prince Edward and, later that October, her father, Maharaja Duleep Singh, also died in Paris.

In 1902, Princess Bamba travelled to Chicago to study medicine at Northwestern University, but the school closed after the trustees decided that women as doctors were not successful. Disappointed, she returned to London and frequently expressed her longing to visit India.

That same year, Edward VII was set to be crowned as King of Great Britain, ruler of all British domains beyond the seas, and Emperor of India. Sensing an opportunity, Princess Bamba and her sisters applied for the passes to attend the coronation which was to happen in India at Delhi. Their request was initially ignored, as the Duleep family was banned from entering India.

Princess Bamba demanded a written explanation for their refusal and in response, the Secretary of State for India stated that, due to time constraints, it would be impossible to provide them with suitable accommodation and to make arrangements for their reception. He urged them to postpone their trip. In effect, this meant they were no longer officially banned from traveling to India. Princess Bamba took the opportunity and without a delay, in 1903, she made the arrangements and along with Princess Catherine travelled first, while Princess Sophia followed on a separate ship.

In India, they were warmly welcomed by Punjab’s chiefs and the aristocratic Sikhs, who still held their great-grandfather in high esteem. The sisters travelled to neighbouring cities, where they met their father’s cousins. They embraced their heritage and listened to stories of their royal lineage and its decline.

In Lahore, Princess Bamba purchased a residence in the Shalimar Gardens and appointed Pir Karim Baksh, known as Pir Ji, as her household manager and translator. During her stay, she once fell ill and feared she was being poisoned, prompting her sister, Princess Sophia, to visit. While in Lahore, Princess Bamba and her sister attended ‘parda’ parties, enjoyed dressing in elegant sarees, and supported revolutionaries such as Lala Lajpat Rai in their struggle against colonial rule.

In 1915, Princess Bamba met Lieutenant Colonel David Waters Sutherland, an Australian-born doctor and professor. At the age of forty-six, she married him and received the promised £10,000 settlement from the Government. Three years later, her elder brother Victor passed away, but wartime restrictions prevented her from attending his funeral.

In 1924, Princess Bamba, along with Princess Sophia, travelled to Nasik to collect their grandmother’s remains from the banks of the Godavari River and brought them to Lahore, placing them beside their grandfather Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s tomb. She also assumed responsibility for her brother Frederick’s art collection after he died of a heart attack in 1926, donating part of it to museums in England and bringing the rest to Lahore, where it was kept in Lahore Fort as the Princess Bamba Collection.

Princess Bamba later faced the loss of her husband in 1939, followed by her sisters Catherine in 1942 and Sophia in 1948. Honouring Sophia’s wishes, Bamba took her ashes to India and, in 1949, travelled to Kassel, Germany, to place Catherine’s ashes beside her governess, Lina Schafer’s grave.

She spent her final years at her Lahore home, known as “The Gulzar”, and died of heart failure on March 10, 1957, at the age of 89. She was buried as Princess Bamba Sutherland in a Christian cemetery. Sadly, due to the Partition, no Sikh attended her funeral. Pir Ji conducted a simple service, placing roses from her garden on her grave, with a gravestone inscription she had likely chosen herself:

‘Farq-i-shahi o bandagi barkhast,

Choon qaza-e navishta aayad pish

Gar kisi khak-i murda baz kunad,

Na shanasad tavangar az darvish.’

Until her last breath, Princess Bamba held Punjab in her heart as her sacred inheritance, commanding respect as its rightful Queen. With sharp features and a dusky complexion, she embodied a fierce and unyielding spirit, a living testament to the legacy of her ancestors, whose courage and dignity she carried forward with unwavering pride.

Leave a Comment