It’s time we put paid to the Indian rope trick

One of the many characteristics that define Indian-ness no matter where in the world is the tendency of large numbers of people to believe in the supernatural.

The sheer range of the belief systems prevalent in India and now being exported all over the world thanks to easier travel links and instant communication technologies is bewildering, to say the least.

From astrologers and charmed talisman vendors to jet setting yogis and gurus, there is an unending stream of the purveyors of esoteric “sciences”, charms, “rediscovered” secret knowledge systems and formulas for spiritual uplift, to list only a few, emerging out of India and travelling the world.

And like anywhere else in the world, the temporal world is never far from the highly rarefied spiritual one – especially so in matters of pursuing fame, the trappings of wealth and a fierce desire to spread influence not so much in an evangelical fashion as much as in a style redolent of a multinational corporate, complete with trained franchisees offering packaged nirvana in a range of flavours and courses. All for a cascading range of prices, directed at different classes of clientele.

Levels of education have nothing to do with beliefs. It is only the degree of the fear of the unknown within the individual that mostly drives this. The examples of Indian celebrities, politicians and common people alike who have added an extra alphabet like an ‘e’, ‘k’, ‘r’ or ‘a’ in their names to “improve” their luck factor after advice from such practitioners are legion.

It gets even more temporal. In an increasingly competitive spiritual world it becomes imperative for these players to stand out, position themselves differently from one another, hire public relations agencies and spin doctors to place themselves in editorials and take out advertisements in the media with all kinds of inducements and promises.

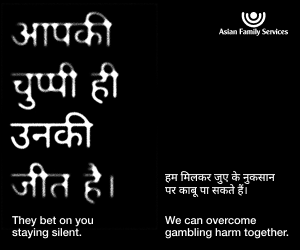

In fact that is exactly what has been happening in ethnic Indian media outlets in New Zealand. Huge advertisements of gurus, babas, astrologers, yogis and tantriks fill a substantial volume of the advertisement space in publications catering to Indians and people of South Asian stock in New Zealand, Indian Weekender included.

It is not that such beliefs do not persist in other cultures – sure, there are ads for clairvoyants, palm readers and soothsayers even in the mainstream New Zealand media. But it is just that they are far more pronounced in South Asian culture, which is what makes this whole business stand out so prominently and at times embarrassingly when these agents of the spiritual world try to outdo each other with promises that are plainly ludicrous.

This problem became so serious in India in the early 1950s, that the nascent Indian Parliament passed an act to legally curb ads that promised magical remedies. It is called the Drugs and Magic Remedies (Objectionable Advertisement) Act, 1954. Promising magical remedies, therefore, is prosecutable under Indian law. Even so, people find creative ways of circumventing the law and the Indian media is awash with such ads.

In any case, there is no recourse to such a law here and so astrologers and tantriks, mostly those visiting here from the Indian subcontinent, have a free rein to promise the moon (and alter your stars). For publications like ours, there is no case for legally refusing paid ads so long as they do not outrage public decency or cause public disorder. They are like any other advertiser since they are paying for the space they hire.

The embarrassingly overpromising nature and tacky quality of these ads that have been appearing here even prompted Indian High Commissioner Admiral (Retd) Sureesh Mehta to publicly state at a function in Auckland last month that Indian papers must eschew carrying such ads, even offering to subsidise the publications to compensate for lost revenue.

A week later, a mainstream television news channel carried out a sting operation catching some of these so-called astrologers and tantriks on camera doling out highly questionable remedies to the programme’s actors.

Subsidy or not, Indian Weekender, starting this anniversary issue, has now taken a decision not to accept for publication ads that make magical promises and remedies, using guidelines under the Indian Drugs and Magic Remedies Act for reference.

One of the many characteristics that define Indian-ness no matter where in the world is the tendency of large numbers of people to believe in the supernatural.

The sheer range of the belief systems prevalent in India and now being exported all over the world thanks to easier travel links and...

One of the many characteristics that define Indian-ness no matter where in the world is the tendency of large numbers of people to believe in the supernatural.

The sheer range of the belief systems prevalent in India and now being exported all over the world thanks to easier travel links and instant communication technologies is bewildering, to say the least.

From astrologers and charmed talisman vendors to jet setting yogis and gurus, there is an unending stream of the purveyors of esoteric “sciences”, charms, “rediscovered” secret knowledge systems and formulas for spiritual uplift, to list only a few, emerging out of India and travelling the world.

And like anywhere else in the world, the temporal world is never far from the highly rarefied spiritual one – especially so in matters of pursuing fame, the trappings of wealth and a fierce desire to spread influence not so much in an evangelical fashion as much as in a style redolent of a multinational corporate, complete with trained franchisees offering packaged nirvana in a range of flavours and courses. All for a cascading range of prices, directed at different classes of clientele.

Levels of education have nothing to do with beliefs. It is only the degree of the fear of the unknown within the individual that mostly drives this. The examples of Indian celebrities, politicians and common people alike who have added an extra alphabet like an ‘e’, ‘k’, ‘r’ or ‘a’ in their names to “improve” their luck factor after advice from such practitioners are legion.

It gets even more temporal. In an increasingly competitive spiritual world it becomes imperative for these players to stand out, position themselves differently from one another, hire public relations agencies and spin doctors to place themselves in editorials and take out advertisements in the media with all kinds of inducements and promises.

In fact that is exactly what has been happening in ethnic Indian media outlets in New Zealand. Huge advertisements of gurus, babas, astrologers, yogis and tantriks fill a substantial volume of the advertisement space in publications catering to Indians and people of South Asian stock in New Zealand, Indian Weekender included.

It is not that such beliefs do not persist in other cultures – sure, there are ads for clairvoyants, palm readers and soothsayers even in the mainstream New Zealand media. But it is just that they are far more pronounced in South Asian culture, which is what makes this whole business stand out so prominently and at times embarrassingly when these agents of the spiritual world try to outdo each other with promises that are plainly ludicrous.

This problem became so serious in India in the early 1950s, that the nascent Indian Parliament passed an act to legally curb ads that promised magical remedies. It is called the Drugs and Magic Remedies (Objectionable Advertisement) Act, 1954. Promising magical remedies, therefore, is prosecutable under Indian law. Even so, people find creative ways of circumventing the law and the Indian media is awash with such ads.

In any case, there is no recourse to such a law here and so astrologers and tantriks, mostly those visiting here from the Indian subcontinent, have a free rein to promise the moon (and alter your stars). For publications like ours, there is no case for legally refusing paid ads so long as they do not outrage public decency or cause public disorder. They are like any other advertiser since they are paying for the space they hire.

The embarrassingly overpromising nature and tacky quality of these ads that have been appearing here even prompted Indian High Commissioner Admiral (Retd) Sureesh Mehta to publicly state at a function in Auckland last month that Indian papers must eschew carrying such ads, even offering to subsidise the publications to compensate for lost revenue.

A week later, a mainstream television news channel carried out a sting operation catching some of these so-called astrologers and tantriks on camera doling out highly questionable remedies to the programme’s actors.

Subsidy or not, Indian Weekender, starting this anniversary issue, has now taken a decision not to accept for publication ads that make magical promises and remedies, using guidelines under the Indian Drugs and Magic Remedies Act for reference.

Leave a Comment