Why Gandhi was a Mahatma

A few years ago, when I was at the University of Waikato, a visiting German student asked me what I thought of Gandhi. I said I considered him great. A young Indian student who was with us respectfully – he had respect for my grey hair – begged to differ. Though he was very respectful he was quite firm in his conviction that Gandhi was not great. It again reminded me of how the people’s perception of Gandhi in India has changed.

Indians now feel that some of the problems there today (like Kashmir for instance) are the legacy left behind by Gandhi. If Gandhi had not backed Nehru to the leadership of the new nation over the firmer and more decisive Sardar Patel there would also not have been a dynastic rule there is what many of the younger generation contend (though it must be said that the descendants of Nehru have always been elected by the people).

With the advantage of hindsight even if one admits that Gandhi was wrong in some of the decisions he made for the new nation, it perhaps only proves that he was a poor politician. There are other achievements that made him a Mahatma still. What I am going to highlight today are some of these other achievements.

Apart from fighting against the might of the British Empire (the sun literally never set on the British Empire in those days. When it was setting in England it was rising in Fiji, through which ran the International Dateline!). He also fought against the evils that he noticed in India. One of the greatest evils was untouchability. This was a direct result of the caste system in India.

The caste system originated with people being grouped together according to their abilities and inclinations. So people who were interested in intellectual pursuits and had spiritual inclinations became the Brahmins, the highest caste. This indicates the importance Indians gave from time immemorial to spirituality over everything else. The physically strong people who were good at fighting became the ruling class, the Kshatriyas. The third group comprised the Vaishyas or the business people while the agriculturalists became the fourth group, the Sudras. Those who did not fit into any of these categories became the last group or the Panchamas (meaning the fifth) and they did all the menial work for the others.

Over a time these castes became hereditary and the Panchamas were treated as inferior by all others. They were discriminated against in many ways and they came to be treated as less than human. They were considered untouchable until Mahatma Gandhi came on the scene and worked to elevate them from their lowly position. He gave them a new name which itself gave them a new status, ‘Harijans’, which meant ‘people of God’. Gandhi worked throughout to eliminate casteism and he was able to inspire a whole generation of people to join him in his struggle for a new India.

The segregation practised against the Harijans (who used to be known as the pariahs) also forbade them to enter Hindu temples for worship. The credit for emancipating them by changing these inhuman practices goes to Gandhiji. Today, more than sixty years after Gandhiji’s death, vestiges of this segregation still persists so one can imagine the great struggle that he had to wage to bring about changes in the Indian society.

Gandhiji gave self-respect not only to the Harijans but to all the Indians who after decades of colonial rule looked upon everything foreign as superior. This was a deliberate plot by the English to subdue the Indians as Lord Macualay had realised that that was the only way to subjugate them: “ … if the Indians think that all that is foreign and English is good and greater than their own, they will lose their self esteem, their native culture and they will become what we want them, a truly dominated nation” (Address to the British Parliament, 2 February, 1835).

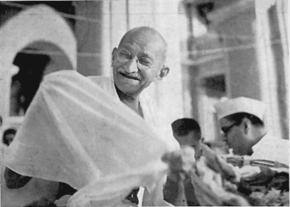

This was done in many ways. There used to be stories of how the British cut off the thumbs of the muslin weavers of north India who wove finer clothes than that produced by the mills in Lancashire. Gandhiji taught his followers to boycott foreign clothes and weave their own cloth. This is why he is always shown with a Charka, the wheel for spinning. This led to the popularity of the khadi, the hand woven material. Even today in India you will find some old people who only wear khadi because they became so used to this coarse, thick material that anything else now seems too flimsy for them.

After Independence the government of India promoted homemade goods by banning foreign goods. Later this led to a craze for everything foreign. But it also encouraged Indian handicrafts and manufacturing industries. Over the years Indian goods improved in quality and with the easing of restrictions on foreign exchange when Indians were again able to buy foreign goods easily they realized that their home made products are as good as the rest if not better.

So today Indians do not look up to everything foreign as superior but are able to appreciate the greatness of their own heritage. They can hold their own against the world in the knowledge that they are inferior to none. This is the proud legacy of Gandhiji. Indeed he was a true Mahatma (A Great Soul).

A few years ago, when I was at the University of Waikato, a visiting German student asked me what I thought of Gandhi. I said I considered him great. A young Indian student who was with us respectfully – he had respect for my grey hair – begged to differ. Though he was very respectful he was quite...

A few years ago, when I was at the University of Waikato, a visiting German student asked me what I thought of Gandhi. I said I considered him great. A young Indian student who was with us respectfully – he had respect for my grey hair – begged to differ. Though he was very respectful he was quite firm in his conviction that Gandhi was not great. It again reminded me of how the people’s perception of Gandhi in India has changed.

Indians now feel that some of the problems there today (like Kashmir for instance) are the legacy left behind by Gandhi. If Gandhi had not backed Nehru to the leadership of the new nation over the firmer and more decisive Sardar Patel there would also not have been a dynastic rule there is what many of the younger generation contend (though it must be said that the descendants of Nehru have always been elected by the people).

With the advantage of hindsight even if one admits that Gandhi was wrong in some of the decisions he made for the new nation, it perhaps only proves that he was a poor politician. There are other achievements that made him a Mahatma still. What I am going to highlight today are some of these other achievements.

Apart from fighting against the might of the British Empire (the sun literally never set on the British Empire in those days. When it was setting in England it was rising in Fiji, through which ran the International Dateline!). He also fought against the evils that he noticed in India. One of the greatest evils was untouchability. This was a direct result of the caste system in India.

The caste system originated with people being grouped together according to their abilities and inclinations. So people who were interested in intellectual pursuits and had spiritual inclinations became the Brahmins, the highest caste. This indicates the importance Indians gave from time immemorial to spirituality over everything else. The physically strong people who were good at fighting became the ruling class, the Kshatriyas. The third group comprised the Vaishyas or the business people while the agriculturalists became the fourth group, the Sudras. Those who did not fit into any of these categories became the last group or the Panchamas (meaning the fifth) and they did all the menial work for the others.

Over a time these castes became hereditary and the Panchamas were treated as inferior by all others. They were discriminated against in many ways and they came to be treated as less than human. They were considered untouchable until Mahatma Gandhi came on the scene and worked to elevate them from their lowly position. He gave them a new name which itself gave them a new status, ‘Harijans’, which meant ‘people of God’. Gandhi worked throughout to eliminate casteism and he was able to inspire a whole generation of people to join him in his struggle for a new India.

The segregation practised against the Harijans (who used to be known as the pariahs) also forbade them to enter Hindu temples for worship. The credit for emancipating them by changing these inhuman practices goes to Gandhiji. Today, more than sixty years after Gandhiji’s death, vestiges of this segregation still persists so one can imagine the great struggle that he had to wage to bring about changes in the Indian society.

Gandhiji gave self-respect not only to the Harijans but to all the Indians who after decades of colonial rule looked upon everything foreign as superior. This was a deliberate plot by the English to subdue the Indians as Lord Macualay had realised that that was the only way to subjugate them: “ … if the Indians think that all that is foreign and English is good and greater than their own, they will lose their self esteem, their native culture and they will become what we want them, a truly dominated nation” (Address to the British Parliament, 2 February, 1835).

This was done in many ways. There used to be stories of how the British cut off the thumbs of the muslin weavers of north India who wove finer clothes than that produced by the mills in Lancashire. Gandhiji taught his followers to boycott foreign clothes and weave their own cloth. This is why he is always shown with a Charka, the wheel for spinning. This led to the popularity of the khadi, the hand woven material. Even today in India you will find some old people who only wear khadi because they became so used to this coarse, thick material that anything else now seems too flimsy for them.

After Independence the government of India promoted homemade goods by banning foreign goods. Later this led to a craze for everything foreign. But it also encouraged Indian handicrafts and manufacturing industries. Over the years Indian goods improved in quality and with the easing of restrictions on foreign exchange when Indians were again able to buy foreign goods easily they realized that their home made products are as good as the rest if not better.

So today Indians do not look up to everything foreign as superior but are able to appreciate the greatness of their own heritage. They can hold their own against the world in the knowledge that they are inferior to none. This is the proud legacy of Gandhiji. Indeed he was a true Mahatma (A Great Soul).

Leave a Comment