Fiji General Elections 2018: What you need to know

Fiji is gearing up for its second national election since returning to the parliamentary-democracy four years ago in 2014 on November 14, next month.

In the last general election held in September 2014, Fiji First, led by current Prime Minister Josaia Voreqe Bainimarama won with 32 seats, followed by the Social Democratic Liberal Party (SODELPA) (15) and the National Federation Party (3).

Earlier Prime Minister Bainimarama had met President Major-General (Retired) Jioji Konusi Konrote on Sunday, September 30, immediately after returning from the United Nations Summit, who further issued an order dissolving the current Parliament.

“His Excellency the president of the Republic of Fiji, on the advice of the Honourable Prime Minister, has dissolved parliament on 30 September 2018,” the South Pacific Island’s government said in a statement.

The government of Fiji has invited India to co-lead the Multinational Observer Group along with Australia and Indonesia.

Voter registration

Voter registration has been closed at 6 pm, Monday, October 1, on the day of issue of the writ, calling for elections. The total number of registered voters as at September 17, 2018, stands at 634,120 out of which 314,686 are females and 319,434 are males.

In 2014, there was 84 per cent voter turnout and 0.75 per cent of invalid votes.

Political Party registration

Eight political parties have been registered by the Fijian Elections Office (FEO) and are eligible to contest in the 2018 general election. This was confirmed by Suresh Chandra, the chairman of the Electoral Commission, in a press conference at the Fijian Elections Office on Monday, October 1.

The eight political parties are Fiji First, Social Democratic Liberal Party, (SODELPA) National Federation Party (NFP), Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), Fiji Labour Party (FLP), Unity Fiji Party (UFP), Hope Party and Freedom Alliance Party.

Important Dates

-

October 2 – 15: The candidate nominations opened on October 2 and will continue till 12 p.m. Monday, October 15.

-

October 16, 2018, candidate nominations withdrawals by 12 p.m.

-

October 16, 2018, candidate nominations objections and appeals close by 4 p.m.

-

October 19, 2018, National candidate ball draw or earlier as determined by the Fijian Elections Office

-

October 24, 2018, postal voting applications close by 5 p.m.

-

November 5, 2018, pre-poll voting begins

-

November 10, 2018, pre-poll voting ends

-

November 12, 2018, media blackout on campaigning commences at 7.30am

-

November 14, 2018, is the Election Day and voting will be from 7.30am to 6 p.m. and in the night the provisional results will be progressively released from 6 p.m.

The current political landscape in Fiji

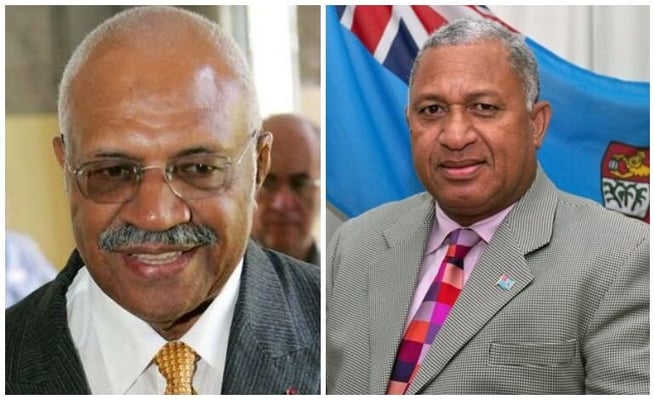

According to many observers of Fiji-politics, the current Prime Minister Mr Bainimarama, who formed the first post-coup democratically elected government, after taking 60 per cent of the vote in the 2014 general election continues to lead opinion polls since then.

The closest political challenger to Mr Bainimarama’s Fiji First is Sitiveni Rabuka’s SODELPA, which has 15 seats in the current parliament.

Interestingly both leaders are coup instigators.

While Mr Rabuka instigated the first coup in 1987, which according to many observers had destabilised the progress of democracy when it was still in its infancy in the South island nation.

Mr Bainimarama on the other hand first seized power in 2006 before being elected as first post-coup leader in elections in 2014.

National Federation Party (NFP), which has a small presence in the last parliament with three seats, is Fiji’s oldest political party. The leader of the party is Biman Prasad, a professor of economics at the University of the South Pacific, who had resigned to pursue a political career.

National Federation Party (NFP) leader Biman Prasad (Image: DNA India)

National Federation Party (NFP) leader Biman Prasad (Image: DNA India)

A peek into Fiji’s socio-political history

One remarkable fact about Fiji’s socio-political history is that for outsiders, there appears to be racial strife between two major ethnicities – native Fijians and Indo-Fijians – something that is strongly refuted and challenged by people from Fiji.

Almost every Fijian spoken to by this reporter for this story had strongly refuted the commonly perceived outsider’s view about the existence of some kind of racial strife in Fiji. In their worldview, everything is serene in Fiji, especially in the countryside where people co-exists amicably in life around farms.

Despite this repeated claim, many observers note that inter-race relations and their struggle for the capture of power were at the centre of at least one coup, if not all the four coups dominating the short political history of Fiji after gaining independence. There has been a huge exodus of Indians from Fiji, especially after the coups of 1987 and 2000, fearing loss of life and persecution.

To this end, a quick peek into Fiji’s socio-political history is in the order.

Fiji got independence from the British colonial rule in 1970, at least after hundred years of colonial rule, and not before the existing social fabric of the remote South Pacific Island was irreversibly changed, in a relatively short span of time for the magnitude of change imposed.

The colonial British had imported a large number of indentured labourers from India to work on the sugarcane plantation (about 60,000 workers were imported from India to Fiji in the period of 35 years by 88 voyages made by 42 ships).

This was a considerable number for a remote island in South Pacific, and since then the racial tension between Indians and their descendants, who made Fiji as their new home, and the native Fijians have always been existent in the island nation.

However, surprisingly, the racial tension was seemingly not prevalent in the socio-economic fabric of the nation, where people to people relations in everyday life is relatively serene.

It is the politics, and the struggle to capture power in this South Pacific heaven that has given the political players an opportunity to exploit the seeming disquiet around the relations between the two ethnic communities.

Politics in Fiji, like everywhere else in the world, is complex. However, it is the speed of change or the swing instability to stability and the vice versa that makes politics in Fiji more fascinating.

The Indian Weekender will strive to bring more coverage and in-depth analysis in the lead up to the Fiji elections.

Fiji is gearing up for its second national election since returning to the parliamentary-democracy four years ago in 2014 on November 14, next month.

In the last general election held in September 2014, Fiji First, led by current Prime Minister Josaia Voreqe Bainimarama won with 32 seats, followed...

Fiji is gearing up for its second national election since returning to the parliamentary-democracy four years ago in 2014 on November 14, next month.

In the last general election held in September 2014, Fiji First, led by current Prime Minister Josaia Voreqe Bainimarama won with 32 seats, followed by the Social Democratic Liberal Party (SODELPA) (15) and the National Federation Party (3).

Earlier Prime Minister Bainimarama had met President Major-General (Retired) Jioji Konusi Konrote on Sunday, September 30, immediately after returning from the United Nations Summit, who further issued an order dissolving the current Parliament.

“His Excellency the president of the Republic of Fiji, on the advice of the Honourable Prime Minister, has dissolved parliament on 30 September 2018,” the South Pacific Island’s government said in a statement.

The government of Fiji has invited India to co-lead the Multinational Observer Group along with Australia and Indonesia.

Voter registration

Voter registration has been closed at 6 pm, Monday, October 1, on the day of issue of the writ, calling for elections. The total number of registered voters as at September 17, 2018, stands at 634,120 out of which 314,686 are females and 319,434 are males.

In 2014, there was 84 per cent voter turnout and 0.75 per cent of invalid votes.

Political Party registration

Eight political parties have been registered by the Fijian Elections Office (FEO) and are eligible to contest in the 2018 general election. This was confirmed by Suresh Chandra, the chairman of the Electoral Commission, in a press conference at the Fijian Elections Office on Monday, October 1.

The eight political parties are Fiji First, Social Democratic Liberal Party, (SODELPA) National Federation Party (NFP), Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), Fiji Labour Party (FLP), Unity Fiji Party (UFP), Hope Party and Freedom Alliance Party.

Important Dates

-

October 2 – 15: The candidate nominations opened on October 2 and will continue till 12 p.m. Monday, October 15.

-

October 16, 2018, candidate nominations withdrawals by 12 p.m.

-

October 16, 2018, candidate nominations objections and appeals close by 4 p.m.

-

October 19, 2018, National candidate ball draw or earlier as determined by the Fijian Elections Office

-

October 24, 2018, postal voting applications close by 5 p.m.

-

November 5, 2018, pre-poll voting begins

-

November 10, 2018, pre-poll voting ends

-

November 12, 2018, media blackout on campaigning commences at 7.30am

-

November 14, 2018, is the Election Day and voting will be from 7.30am to 6 p.m. and in the night the provisional results will be progressively released from 6 p.m.

The current political landscape in Fiji

According to many observers of Fiji-politics, the current Prime Minister Mr Bainimarama, who formed the first post-coup democratically elected government, after taking 60 per cent of the vote in the 2014 general election continues to lead opinion polls since then.

The closest political challenger to Mr Bainimarama’s Fiji First is Sitiveni Rabuka’s SODELPA, which has 15 seats in the current parliament.

Interestingly both leaders are coup instigators.

While Mr Rabuka instigated the first coup in 1987, which according to many observers had destabilised the progress of democracy when it was still in its infancy in the South island nation.

Mr Bainimarama on the other hand first seized power in 2006 before being elected as first post-coup leader in elections in 2014.

National Federation Party (NFP), which has a small presence in the last parliament with three seats, is Fiji’s oldest political party. The leader of the party is Biman Prasad, a professor of economics at the University of the South Pacific, who had resigned to pursue a political career.

National Federation Party (NFP) leader Biman Prasad (Image: DNA India)

National Federation Party (NFP) leader Biman Prasad (Image: DNA India)

A peek into Fiji’s socio-political history

One remarkable fact about Fiji’s socio-political history is that for outsiders, there appears to be racial strife between two major ethnicities – native Fijians and Indo-Fijians – something that is strongly refuted and challenged by people from Fiji.

Almost every Fijian spoken to by this reporter for this story had strongly refuted the commonly perceived outsider’s view about the existence of some kind of racial strife in Fiji. In their worldview, everything is serene in Fiji, especially in the countryside where people co-exists amicably in life around farms.

Despite this repeated claim, many observers note that inter-race relations and their struggle for the capture of power were at the centre of at least one coup, if not all the four coups dominating the short political history of Fiji after gaining independence. There has been a huge exodus of Indians from Fiji, especially after the coups of 1987 and 2000, fearing loss of life and persecution.

To this end, a quick peek into Fiji’s socio-political history is in the order.

Fiji got independence from the British colonial rule in 1970, at least after hundred years of colonial rule, and not before the existing social fabric of the remote South Pacific Island was irreversibly changed, in a relatively short span of time for the magnitude of change imposed.

The colonial British had imported a large number of indentured labourers from India to work on the sugarcane plantation (about 60,000 workers were imported from India to Fiji in the period of 35 years by 88 voyages made by 42 ships).

This was a considerable number for a remote island in South Pacific, and since then the racial tension between Indians and their descendants, who made Fiji as their new home, and the native Fijians have always been existent in the island nation.

However, surprisingly, the racial tension was seemingly not prevalent in the socio-economic fabric of the nation, where people to people relations in everyday life is relatively serene.

It is the politics, and the struggle to capture power in this South Pacific heaven that has given the political players an opportunity to exploit the seeming disquiet around the relations between the two ethnic communities.

Politics in Fiji, like everywhere else in the world, is complex. However, it is the speed of change or the swing instability to stability and the vice versa that makes politics in Fiji more fascinating.

The Indian Weekender will strive to bring more coverage and in-depth analysis in the lead up to the Fiji elections.

Leave a Comment